2. Introduction¶

2.1. References to start with¶

We will not follow one text-book. However, it will be good to have a couple of standard references to fall back on for a literature search:

- Two such standard references on machine learning are [russell_artificial_2010] and [bishop_pattern_2007];

- Another reference on this topic with a more mathematical focus is [mohri_foundations_2012].

Furthermore, here are a couple of references which will be helpful for the Python implementations we are about to write during this course:

Official Python 3 documentation [python_development_team_python_2016]. Have a look at the Tutorial chapter.

The Scipy lecture notes [scipy_development_team_scipy_2016] include tutorials on scientific use of Python. The two Python modules will use most often are:

- Numpy: Its documentation can be found here [numpy_development_team_numpy_2016].

- Matplotlib: Its documentation can be found here [matplotlib_development_team_matplotlib_2016]. A good starting point to explore its features is to take a look at the gallery of examples.

If you haven’t already done so, install a Python development environment. Depending on what operating system you run, there are several options:

- All platforms: Anaconda provide a quite painless way to install everything you need for a first start;

- MacOS: Python 2 is already installed. However, to install Python

3, IPython, and for easier installation of additional modules

with

pip, I recommend to either also install Anaconda or use Homebrew; - Linux: Python 2 and 3 should be installed by default. Install

additional modules with

pip.

If you are not already expert enough in using the modules Numpy and Matplotlib, attend to the references above and learn their basic usage.

2.2. Vocabulary and Overview¶

Before we dive into the topic let us settle for a common vocabulary and get an idea about what we would like to achieve with our study. To put machine learning in perspective we shall start very broadly with a discussion of artificial intelligence taken from the very recommendable introduction in [russell_artificial_2010] and afterwards put machine learning and the aims of this lecture in perspective:

What is artificial intelligence (AI)?

For thousands of years, we have tried to understand how we think;

AI even attempts to go a step further:

- it attempts not just to understand but also to build intelligent entities.

AI is one of the newest fields in science and engineering (started after World War II);

Possible definitions:

Acting humanly:

“The art of creating machines that perform functions that require intelligence when performed by people.”

—Kurzweil, 1990

“The study of how to make computers do things at which, at the moment, people are better.”

—Rich and Knight, 1991

Thinking humanly:

“The exciting new effort to make computers think […] machines with minds, in the full and literal sense.”

—Haugeland, 1985

“[The automation of] activities that we associate with human thinking, activities such as decision-making, problem solving, learning […]”

—Bellman, 1978

Acting rationally:

“Computational Intelligence is the study of the design of intelligent agents.”

—Poole et al., 1998

“AI […] is concerned with intelligent behavior in artifacts.”

—Nilsson, 1998

Thinking rationally:

“The study of mental faculties through the use of computational models.”

—Charniak and McDermott, 1985

“The study of the computations that make it possible to perceive, reason, and act.”

—Winston, 1992

Acting humanly: The Turing test approach

In 1950 Turning [turing_i.computing_1950] devised a test to provide a satisfactory operational definition of intelligence;

A computer passes the test if a human interrogator, after posing some written questions, cannot tell whether the written responses come from a person or from a computer;

The computer needs to posses the following features:

- natural language processing: to communicate in, e.g., English

- knowledge representation: to store the information

- automated reasoning: to use the stored information, to answer question, and to draw conclusions

- machine learning: to adapt to new circumstances, and extrapolate and detect patterns

The Turing test remains relevant even today but less from the engineering and more from the philosophical stance, i.e., in the following spirit (taken from [russell_artificial_2010]):

- The quest for “artificial flight” succeeded when the Wright brothers and others stopped imitating birds and started using wind tunnels and learning about aerodynamics.

- Aeronautical engineering texts do not define the goal of their field as making “machines that fly so exactly like pigeons that they can fool even other pigeons.”

Homework

Read Turning’s paper [turing_i.computing_1950] and put it in context with the field of artificial intelligence.

Thinking humanly: The cognitive modeling approach

To tell whether a program “thinks like a human” we need to learn what humanely thinking is:

- Observe our thoughts as the go by;

- Observe persons during a task

- Psychological / Neuroscientific experiments

For our endeavor, however, it will be good practice to keep the fields such as cognitive science, neuroscience, psychology and philosophy separated as long as it is possible.

Thinking rationally: The “laws of thought” approach

Use of logical reasoning and argumentation, for example:

deduction: A general rule applied to a particular case implies a trivial result.

Input Implication Example RULE On a planet its sun rises every day. CASE We are on a planet. RESULT The sun rose every day. The realm of mathematics.

induction: From a trivial result in a particular case we hope to infer the general rule.

Input Implication Example RESULT The sun rose every day. CASE We are on a planet. RULE On a planet its sun rises every day. The realm of science.

abduction: From a general rule and a trivial result we hope to infer the particular case.

Input Implication Example RULE On a planet its sun rises every day. RESULT The sun rose every day. CASE We are on a planet. More seldomly used.

Homework

Discuss which type of reasoning can most readily be learned by a computer.

Discuss why the other two examples of reasonings are more difficult to implement.

Observe yourself in discussions:

What type of arguments do you use? Analogies, examples, experience, interpretations, faith, etc.

Benchmark them w.r.t. deduction and come clean with our dilemma:

- Read Plato’s Apology 21a-d:

“‘When he was forty, there came a curious but crucial episode which changed Socrates’ whole life. What happened shall be told in the words which, by Plato’s account, he himself used at his trial [by which time Socrates was 70 years old (Apology 17d)]. ‘Everyone here, I think, knows Chaerephon,’ he said, ‘he has been a friend of mine since we were boys together; and he is a friend of many of you too. So you know the eager impetuous fellow he is. Well, one day he went to Delphi, and there he had the impudence to put this question – do not jeer, gentlemen, at what I am going to say – he asked, ‘Is anyone wiser than Socrates?’ And the Pythian priestess answered, ‘No one.’ Well, I was fully aware that I knew absolutely nothing. So what could the god mean? for gods cannot tell lies. For some time I was frankly puzzled to get at his meaning; but at last I embarked on my quest. I went to a man with a high reputation for wisdom – I would rather not mention his name; he was one of the politicians – and after some talk together it began to dawn on me that, wise as everyone thought him and wise as he thought himself, he was not really wise at all. I tried to point this out to him, but then he turned nasty, and so did others who were listening; so I went away, but with this reflection that anyhow I was wiser than this man; for, though in all probability neither of us knows anything, he thought he did when he did not, whereas I neither knew anything nor imagined I did.’”

—Plato, Apology 21a-d, Translation by C.E. Robinson

Argue then how we can even learn.

- Read Meno by Socrates at least starting from this passage:

“Meno: And how will you enquire, Socrates, into that which you do not know? What will you put forth as the subject of enquiry? And if you find what you want, how will you ever know that this is the thing which you did not know?

Socrates: I know, Meno, what you mean; but just see what a tiresome dispute you are introducing. You argue that man cannot enquire either about that which he knows, or about that which he does not know; for if he knows, he has no need to enquire; and if not, he cannot; for he does not know the, very subject about which he is to enquire.”

—Plato, Meno, Translation by B. Jowett

Acting rationally: The rational agent approach

Create agents (e.g., computer progams) that operate autonomously, perceive their environment, persist over a prolonged time period, adapt to change, and create and pursue goals.

Making correct inferences (as in the “laws of thought” approach) is the extreme case of being a rational agent.

In many situations, however, correct inferences are not possible, e.g.:

- insufficient understanding of the environment;

- not enough input data to base a decission on.

A rational agent is one that acts so as to achieve the best outcome or, when there is uncertainty, the best expected outcome.

We will go down this road:

The standard of rationality is mathematically well defined and completely general.

We may exploit this, spell out specific designs, and check how they perform in certain environments. For instance:

- The “probably approximatly correct (PAC)” framework

Human behavior, on the other hand, is well adapted for one specific environment and is defined by, well, the sum total of all the things that humans do.

Homework

In the introducion of [russell_artificial_2010] the following questions are put forward:

- “Surely computers cannot be intelligent—they can do only what their programmers tell them.” Is the latter statement true, and does it imply the former?

- Surely animals cannot be intelligent—they can do only what their genes tell them.” Is the latter statement true, and does it imply the former?

- “Surely animals, humans, and computers cannot be intelligent—they can do only what their constituent atoms are told to do by the laws of physics.” Is the latter statement true, and does it imply the former?

What is your opinion?

Influences:

Philosophy:

- Can formal rules be used to draw valid conclusions?

- How does the mind arise from a physical brain?

- Where does knowledge come from?

- How does knowledge lead to action?

Mathematics:

- What are the formal rules to draw valid conclusions?

- What can be computed?

- How do we reason with uncertain information?

Neuroscience:

- How do brains process information?

Psychology

- How do humans and animals think and act?

Computer engineering

- How can we build an efficient computer – the artifact that we want to charge with intelligence?

Control theory and cybernetics:

- How can artifacts operate under their own control?

Linguistics:

- How does language relate to thought?

And finally economics:

- How should we make decisions so as to maximize payoff?

- How should we do this when others may not go along?

- How should we do this when the payoff may be far in the future?

A breakdown of historical periods:

1943–1955: The gestation of artificial intelligence

- Model of artificial neurons by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts in 1943 – see [mcculloch_logical_1943];

- Turning gave lectures on AI as soon as 1947.

1956: The birth of artificial intelligence

- John McCarthy convinced Marvin Minsky, Claude Shannon, and Nathaniel Rochester to help him bring together U.S. researchers interested in automata theory, neural nets, and the study of intelligence at a two-month workshop in Dartmouth.

1952–1969: Early enthusiasm, great expectations

- First problem solvers, game players, theorem provers;

- John McCarthy referred to this period as the “Look, Ma, no hands!” era;

- Creation of LISP;

- Perceptron by Frank Rosenblatt in 1958 [rosenblatt_perceptron:_1958];

- Adalines (adaptive linear neuron) by Bernie Widrow and Marcian Hoff in 1960 [widrow_adapting_1960];

1966–1973: A dose of reality

- Try and error – combinatorial explosion;

- Lack of computational resources.

1969–1979: Knowledge-based systems: The key to power?

- Algorithms using of domain-specific knowledge instead of general-purpose solvers;

- Expert systems for medical diagnosis;

- Incorporation of uncertainty.

1980–present: AI becomes an industry

- Optimization of logistics;

- Sudden boom but only few projects lived up to their expectations;

- AI winter.

1986–present: The return of neural networks

- The back-propagation algorithm for training neural networks was reinvented in [rumelhart_learning_1986];

1987–present: AI adopts the scientific method

- Hidden Markov models;

- Bayesian networks;

1995–present:

The Internet pushes the development of intelligent (?) agents, e.g.:

- chatbots

- recommender systems

- aggregates

Access to computation resources at sufficient speed.

The big data age: Huge amount of labeled training data available, e.g.:

- Dictionaries

- Word corpora on different topics

- Wordnets

- Wikipedia

Founders of AI discontent with current state:

- AI should return to its roots of striving for, in Herbert Simon’s words, “machines that think, that learn and that create.”

State of the art – some examples:

- Spam fighting: Most adaptation done my machine learning algorithms

- Speech recognition: Siri,

- Face recognition: Facebook, Apple Photos, Google Photos

- Game playing: IBM’s deep blue chess player against world champion Garry Kasparov

- Autonomous planning and scheduling: NASA’s mars rover

- Robotic vehicles: Tesla’s self-driven car

- Machine Translation: Google Translate

Homework

- Discuss the difference between understanding and knowing – take as an example the repeating phenomena of the sun rise discussed above.

- From this perspective, discuss why big data is certainly a great resource to have to advance the field of AI but by itself will most likely disappoint us – take for example the human genom.

Note

2016-10-19

Now that we have an overview where about we are, let us discuss the direction of our study. Also we might disappoint the founders such as Simon as we will focus solely on machine learning. However, in our defense we may claim that in whichever direction AI might develop, machine learning will at least be a extremely important stepping stone if not even stay an integral part in the field:

What is machine learning (ML)?

ML is a subfield of AI:

“[Machine learning] gives computers the ability to learn without being explicitly programmed”

—Samuel, 1959

Put differently, one seeks “soft” algorithms which to some extend can adapt themselves to a certain type of task instead of consisting merely of hard-coded logic.

Dealing with large amounts of data:

- structuring data

- finding correlation

- classification of data

- pattern recognition

- data compression

- data driven decision

- adaptation of tasks to data

- extrapolation / prediction

Types:

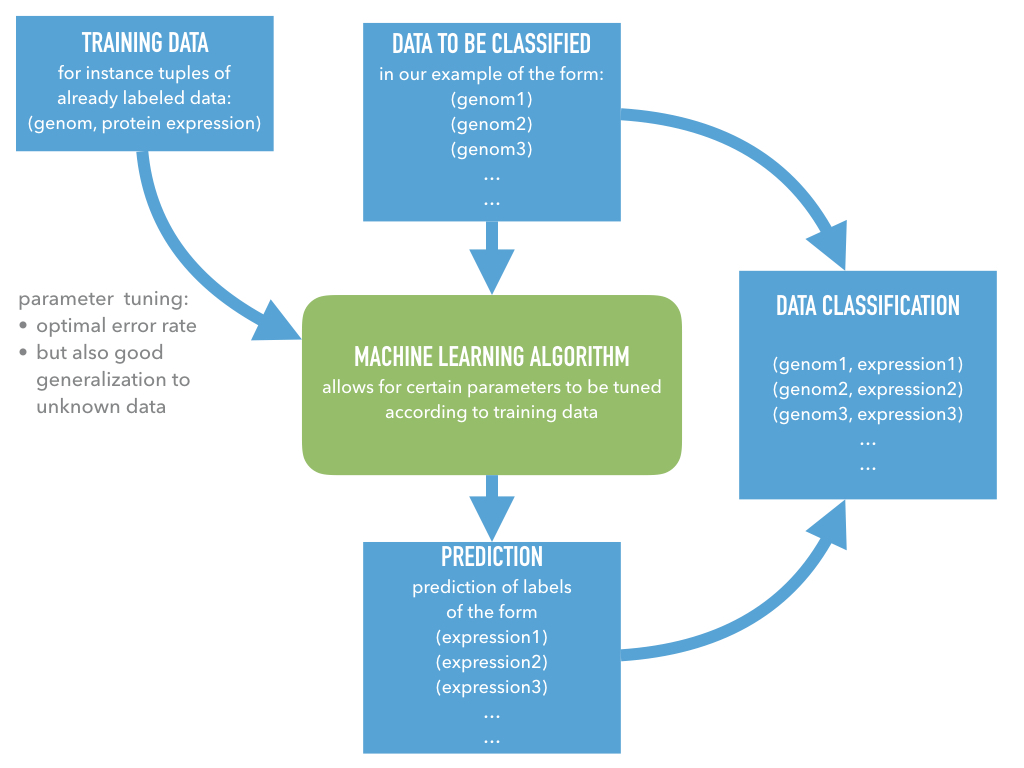

Supervised learning

“Soft” algorithms which are supposed to infer the designated task by inspection of appropriate training data.

Examples:

Classification: prediction of discreet classes, e.g.:

- Email is spam or not;

- Image shows a cat (see article How Many Computers to Identify a Cat? 16,000);

Regression: prediction of continuous parameters, e.g.:

- energy consumption according to learned user behavior

- prediction of a trend according to a given history

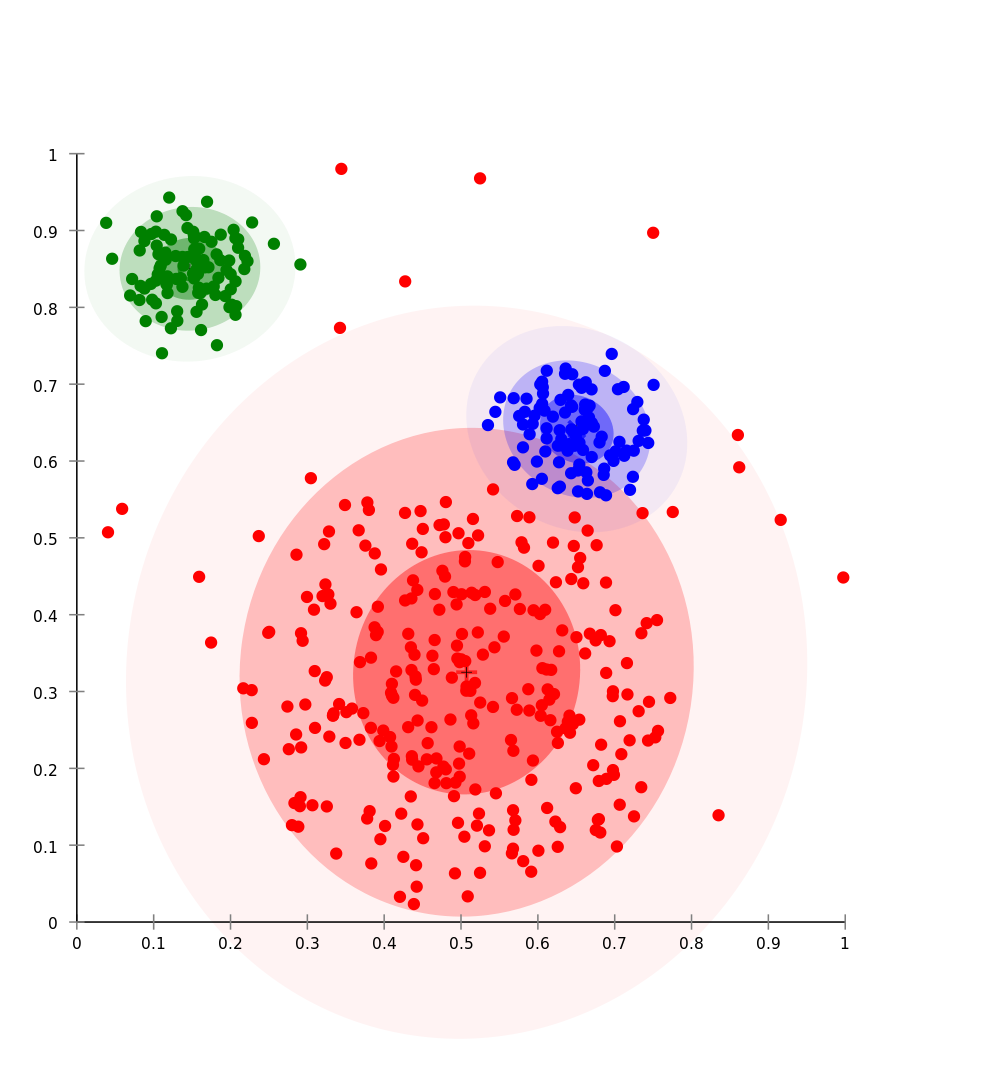

Unsupervised learning

Structuring data into clusters without detailed prior knowledge.

Ficticious example of 2d data points. The color indicates a relation between the data points. From these relations the shaded regions may be inferred by an unsupervised machine learning algorithm. This may be useful when looking for coarse, structural properties of a datat set. (source).

Examples:

- Wordnets: Relationships between words of a natural language;

- Cross-references between documents;

- Data compression and dimensionality reduction.

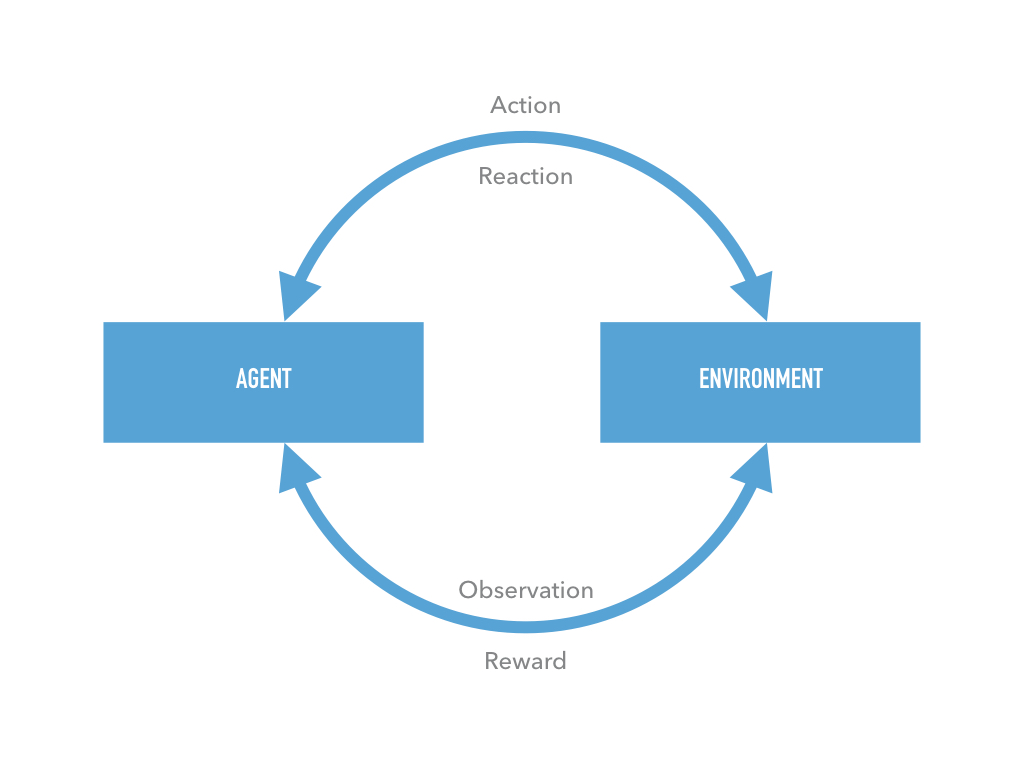

Reinforcement learning

An agent (machine learning program + artifact) learns to fulfill a certain task by, e.g., trial and error. Learning is facilitated by the ability to observe the environment and receive feedback depending on the actions.

Examples:

- Movement of a robot in unknown terrain or under varying conditions;

- Getting high-scores in Atari games like Google Deepmind [mnih_human-level_2015].

Our main focus in this short course will lie on supervised learning using neural networks.